By Harry McCracken

(Scrappy title courtesy of Jerry Beck)

January 2005

I’m not saying he’s the greatest cartoon character of the 1930s–he most definitely isn’t. Despite his current obscurity, he’s not the most forgotten thirties character, either. (Who is? I’ve forgotten.)

But the Charles Mintz studio’s Scrappy is the archetypal obscure 1930s cartoon character–the best example of that particular breed. Consider the evidence:

Nobody fondly remembers him. This country is still teeming with people who were kids when Scrappy cartoons first appeared in theaters. His career lasted a decade, and was accompanied by an array of merchandise, books, and other related paraphernalia. But find me one senior citizen who remembers seeing those shorts. Go on–I dare you. If it wasn’t for obssessed cartoon fans, this character would be toast.

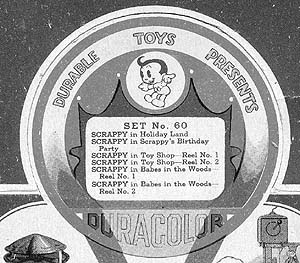

You can’t see his cartoons. In the 1950s, when TV showed all the black-and-white cartoons it could get its hands on, Scrappy was a staple of kids’ programming. (Many surviving prints of his cartoons, have TV titles.) Today, we live in a world in which you can buy Van Beuren cartoons of the same era at a dollar store. Scrappy, however, remains tough to track down, even in bootleg form. He’s the Judge Crater of animation: A once-important personage who just disappeared. (Rumor has it, however, that he–Scrappy, not the judge–has been spotted on Spanish-language TV in recent years.)

And yet, those cartoons are worth seeing. Disclaimer: Not everybody who knows Scrappy loves Scrappy. Historian Ray Pointer of Inkwell Images has told me that he thinks “the overall skill in the animation [in Scrappy cartoons he’s seen] was superior to Disney’s at that time, but concepts and stories are not always as inspired…generally, they are rather ordinary.” Even Scrappy creator Dick Huemer didn’t think particularly highly of the series, reports his son, Richard P. Huemer. (Which is understandable: If I’d co-written Dumbo, I’d be hard-pressed to be prouder of anything else I’d done in my career.)

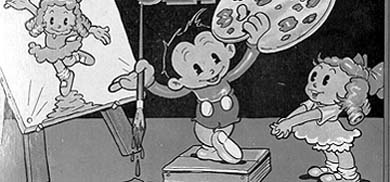

But Scrappy films have something that many forgotten cartoons don’t–a point of view. The character himself is anything but a generically cheerful Mickey Mouse clone a la Bosko or Buddy. Instead, he’s an irritable, short-tempered guy who clearly sees his younger brother, Oopy, as an unmanagable burden. Oopy, somehow, remains high-spirited and optimistic despite Scrappy’s shabby treatment of him. Those are strikingly real-world characterizations, yet ones that I can’t recall seeing in any other vintage animation series. (How many cartoon characters have siblings of any sort?)

Dick Huemer himself, by the way, was an older brother, but didn’t have an Oopyesque kid brother of his own. “Dick was the only boy in his family,” reports Richard P. Huemer. “He had three sisters (Elsie, the eldest; Peggy, the youngest; and Hilda, who died in childhood of rheumatic heart disease). I think Elsie was older than Dick. Basically, I don’t know what served as his model for the interaction between male siblings.”

In their own unassuming way, the strongest Scrappys are also innovative little films. “Let’s Ring Doorbells and The Puppet Murder Case (both 1935) are among the first cartoons to feature montage sequences,” notes pioneering Scrapologist Paul Etcheverry, the co-author of 1981’s Animania article on the character. “I’m not sure who got there first–Hugh Harman (Circus Daze) and Frank Tashlin (almost every B&W Porky Pig he directed) were also working concurrently along similar lines. In any case, you have to reach back to the most far-out segments in the Fleischer and Messmer silents to come up with anything like what these guys were doing.”

Like most of the best studio cartoons of the 1930s, the most memorable Scrappys have a strong feel of that decade. Scrappy didn’t just acknowledge the Depression, he monetized it–by starting a fleabag hotel for homeless animals (The Flop House, 1932). In Scrappy’s Television (1934), he invented a TV–in the thirties, everyone was trying to do that–but it showed Ed Wynn and Primo Carnera. He even went to the Chicago World’s Fair and encountered FDR, Mussolini, Gandhi, and Durante there (The World’s Affair, 1933). You could produce a documentary about the decade based entirely on Scrappy clips, and while it wouldn’t be all-encompassing, it sure would be entertaining.

You could also trace most important animation trends of the 1930s simply by following the character’s career: He started off as an off-kilter, rubber-hose imitation of Mickey Mouse, morphed into a more-realistic-but-less-appealing kid, and ended up suffering the ignominy of being a minor player in his own films. (A cartoon character’s day in the sun is over when he’s reduced to narrating newsreel spot gags, as Scrappy did in 1937’s Scrappy’s News Flashes.)

Almost any theme that was fodder for cartoon humor in the thirties showed up in Scrappy cartoons, sometimes early (he hunted ducks before Porky and had a trailer before Mickey) and sometimes late (two years after Mickey held a band concert, so did Scrappy.) And at various times, the series seemed influenced by the work of Disney, Harman-Ising, Warner Bros. and Fleischer.

Especially Fleischer: If you love the essential strangeness of Betty Boop, Popeye, or Out of the Inkwell, you need to get acquainted with the dreamy, peculiar world of early Scrappy cartoons. Their Fleischeresque flavor isn’t surprising given that their creators, Dick Huemer, Sid Marcus, and Art Davis, were Fleischer transplants who worked in a Fleischer-like fashion, more or less inventing the cartoons’ stories and gags as they went along. Nobody tried very hard to match anyone else’s drawing style, which added to the dreamlike quality.

At times, Scrappy cartoons are bizarrely postmodern (I hate that word, but it’s accurate), especially for cartoons made so long ago. Characters often speak as if reciting from overly melodramatic scripts; Scrappy was known to call Oopy “young fella,” which is a damned odd way to refer to one’s own brother. Then there’s Scrappy’s Theme Song (1934), whose title is self-explanatory–I don’t know of another thirties series which would have self-referentially spun an entire short from its hero composing and popularizing a mindless song about himself.

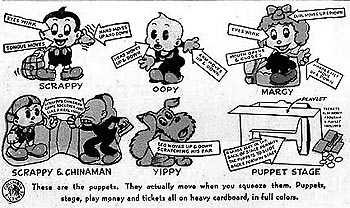

The weirdness that is Scrappy stretches beyond the content of the films. Most of his merchandise–and there was a lot of it–has a mysterious, sometimes disturbing quality. What other character starred in a puppet-theater premium that let you dramatize his brawl with an angry Chinese man? Who else promoted the importance of being adequately insured? Not Mickey Mouse, Bosko, or even Betty Boop. And because so little is remembered about Scrappy, there’s still plenty left to discover.

But daunting obstacles stand between Scrappy and the attention he deserves. For one thing, there’s little reason to be optimistic that his films will reappear anytime soon–why would Sony, his current caretaker, invest in the rerelease of films that almost nobody remembers and only a few hardcore animation fans want to see?

And yet Scrappy’s ouevre hasn’t fallen into the public domain, either. So he can’t be the subject of unauthorized-but-legit releases such as those we’ve seen of Fleischer, Iwerks, and Van Beuren films.

He can, however, be the subject of a Web site. Welcome to Scrappyland, where Scrappy is documented, analyzed, and sometimes admired….but most of all, simply remembered.

–Harry McCracken, January 2005

Any one thought of a petition to Sony to rerelease them?

I could get 10-12 signatures. Maybe more. If 1000s did this we might have some pull! Just curious.

David Cox

Very happy to have found this site. I’m 65, and for fifty years I have been asking if anyone else my age remembers the song, “Congratulations to you, Scrappy.” They all look at me like I’m crazy. Finally I can show my kids that Scrappy isn’t just a figment of my imagination. Grew up in the New York area and these 30s cartoons (Scrappy, Popeye, Betty Boop, Koko, Gabby, Krazy Kat et al) repeated over and over on the cartoon shows of the 50s and early 60s are what sparked my lifelong interest in, and love of, classic animation. Thanks for the great memories.

What about Krazy Kat?

I remember Scrappy fondly from ‘50s TV. No one I’ve asked remembers him. It was great to find this sitt, even with so few folks interested. I remember the Scrappy episode in which he chases and catches a butterfly with a butterfly net — and then releases him.

Scrappy has become somewhat influential in my life. Even if I was born DECADES after the series was ever remotely popular in the mainstream, I still find joy in watching the series. Sometimes, during long car rides with my family, I’ll let my little sister watch Scrappy to pass the time. Scrappy and Oopy influenced my characters Floyd & Tyke Foxes, albeit in a much more wholesome way. You won’t see Floyd tossing Tyke into a lake. I even own a few of the 1934 Glow Light covers. Me being born in the 21st Century, connecting to this long lost Star of Animation’s Golden Age, proves that Scrappy has an appeal with All Ages.

Never heard of this toon. But I really love his design its beautyful a total forgotten masterpiece! Somebody should revive this old classic you know buy its rights and create good cartoon episodes and become a cinema’s legend.