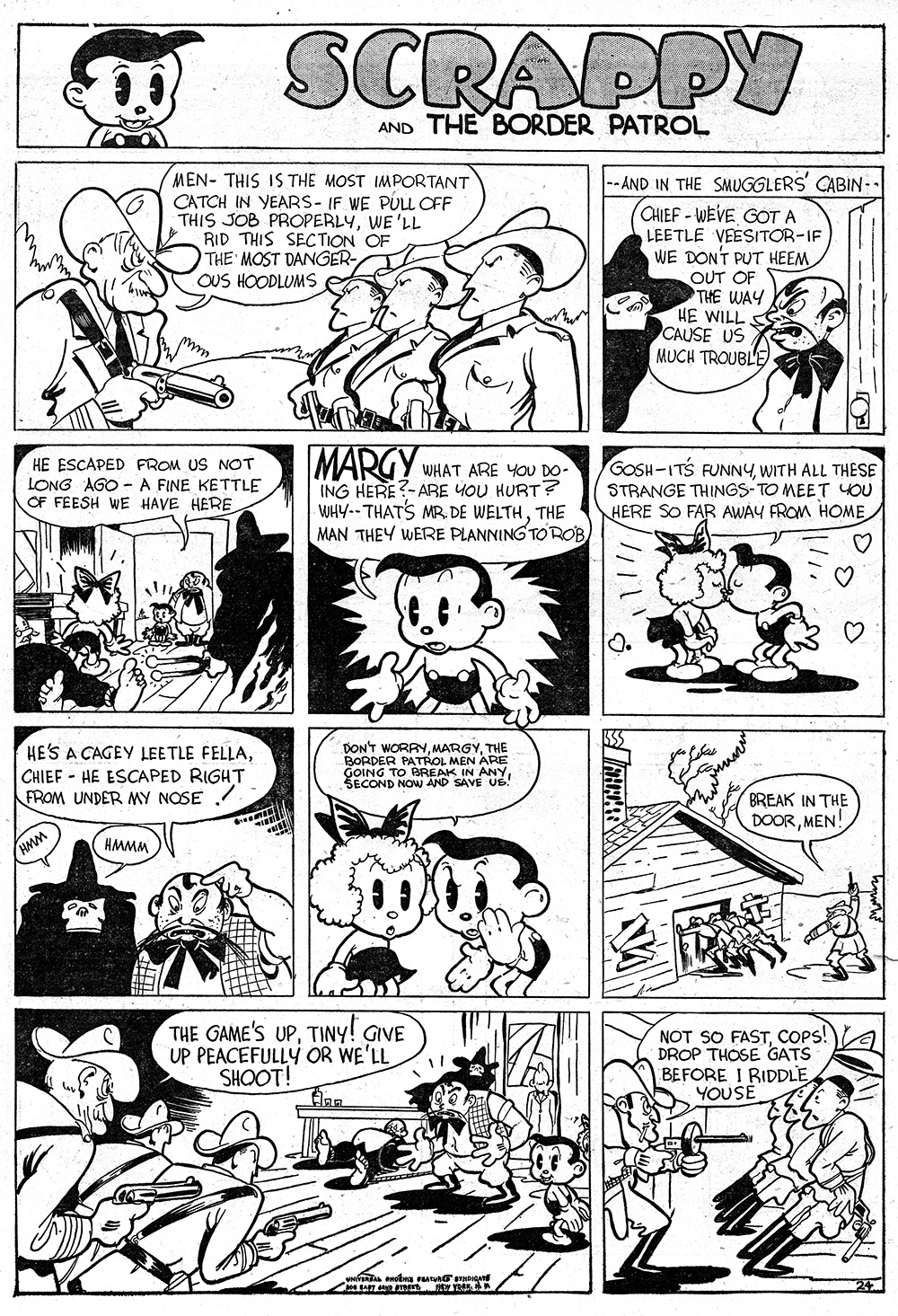

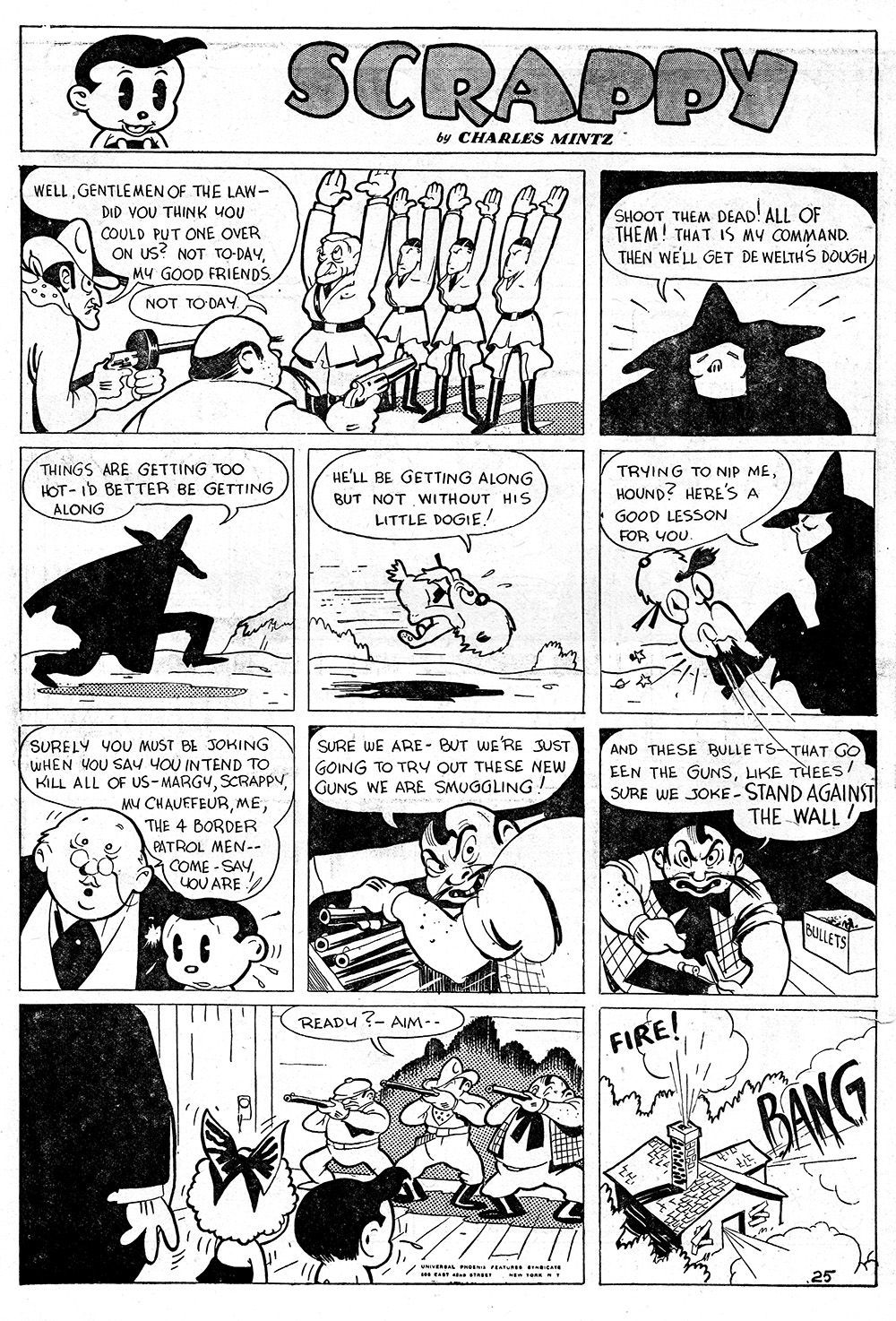

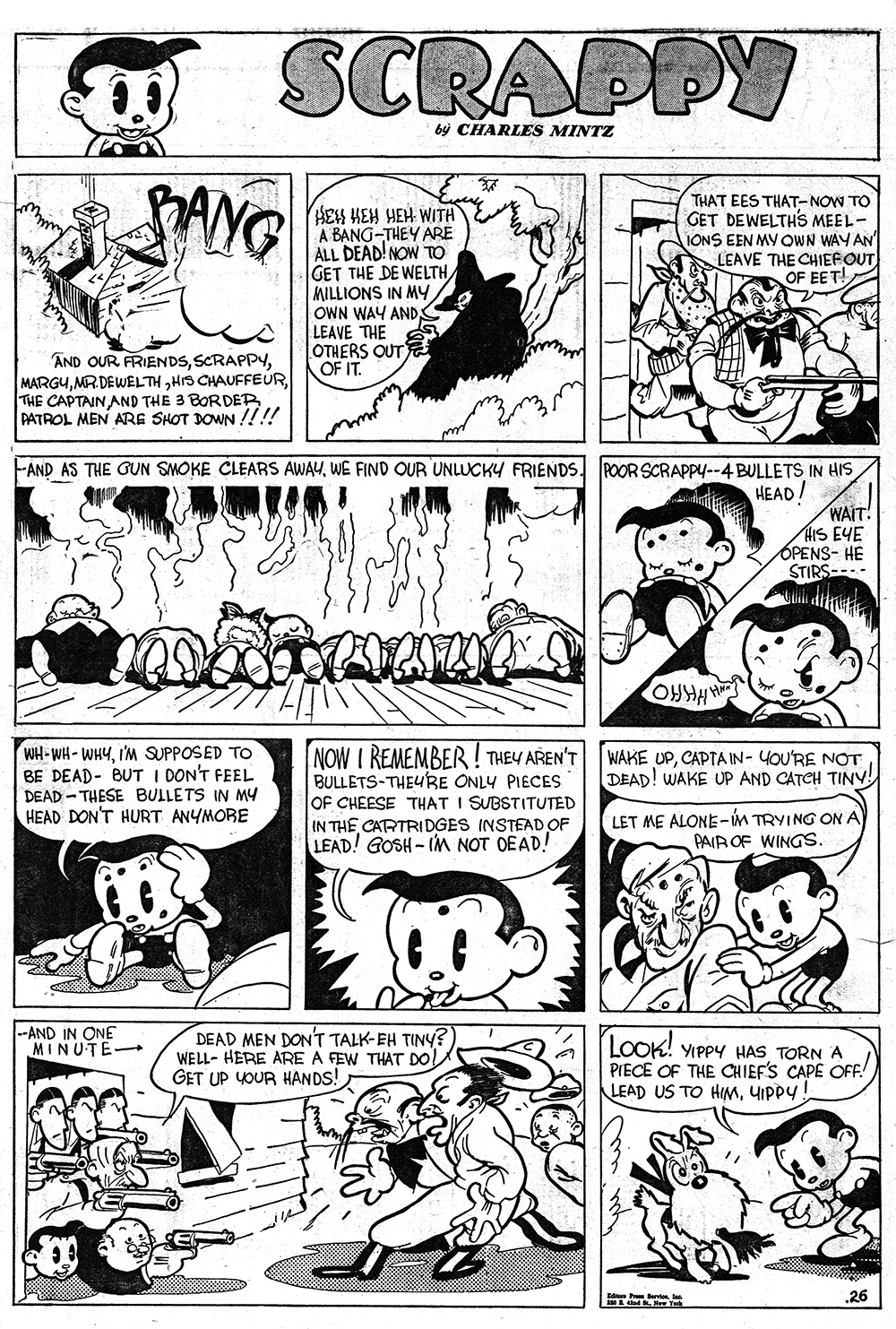

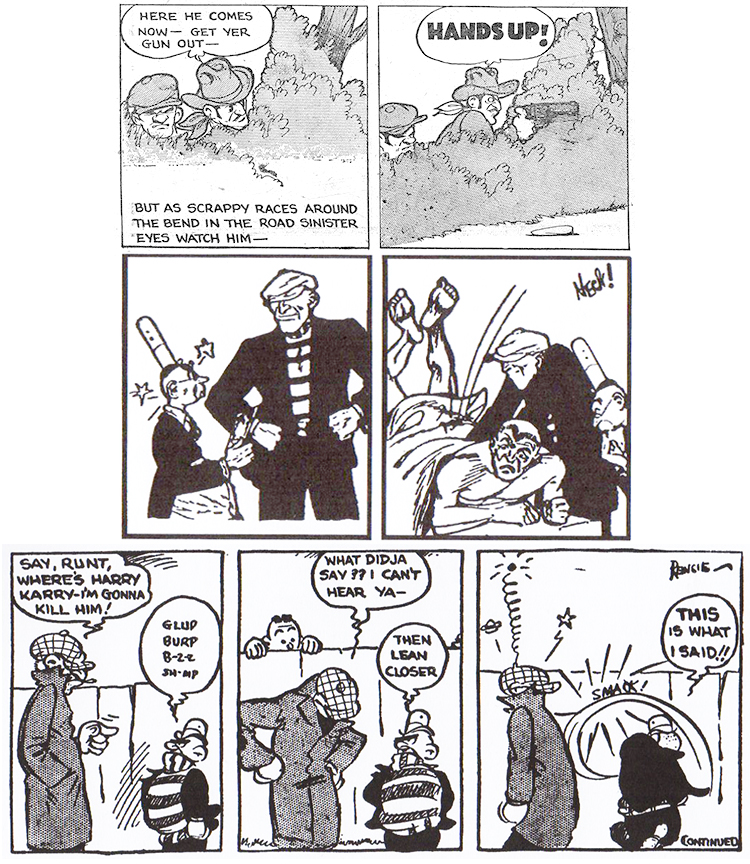

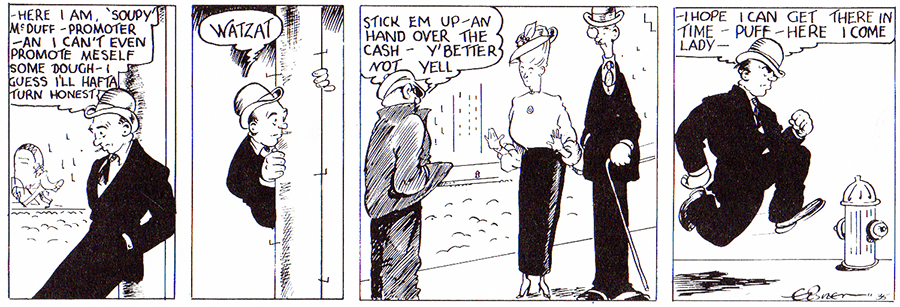

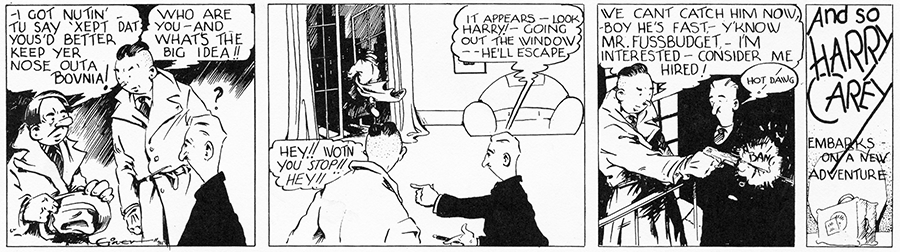

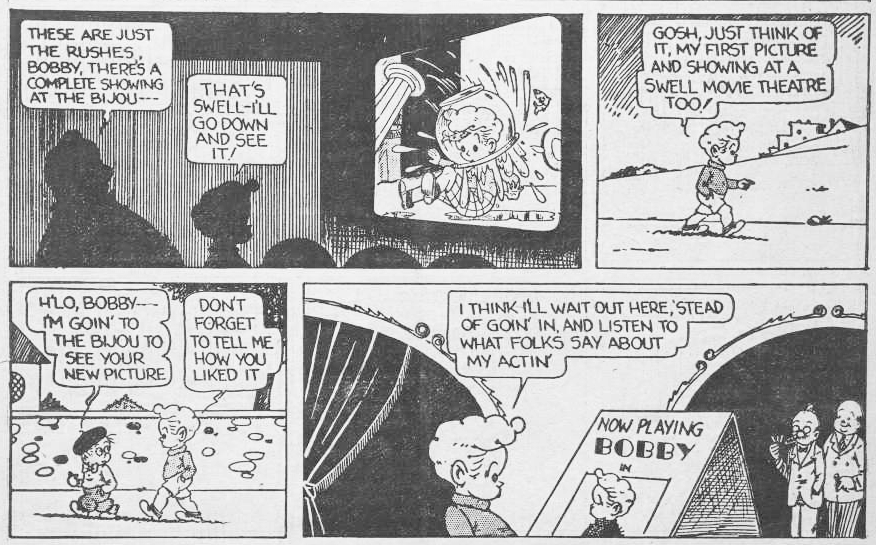

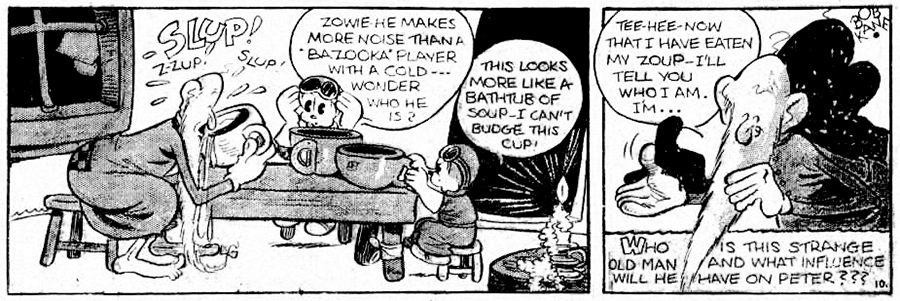

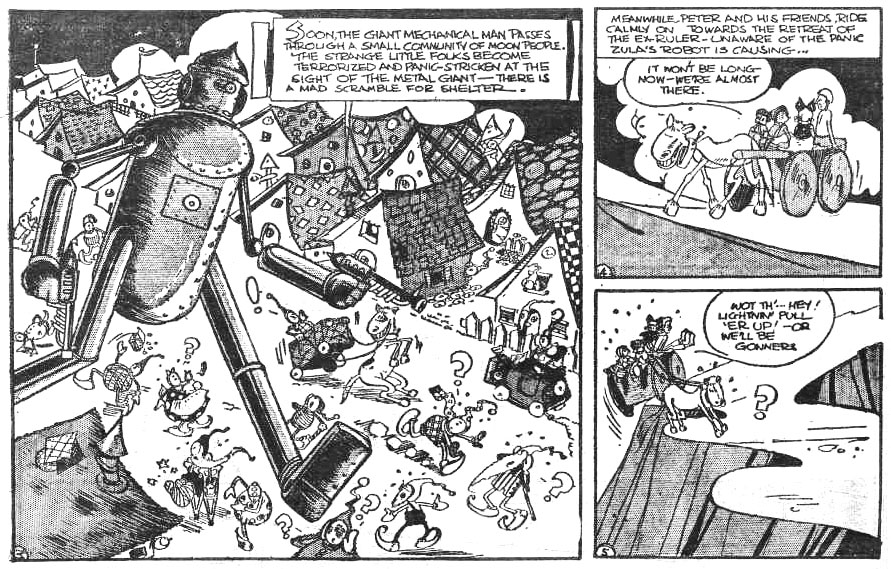

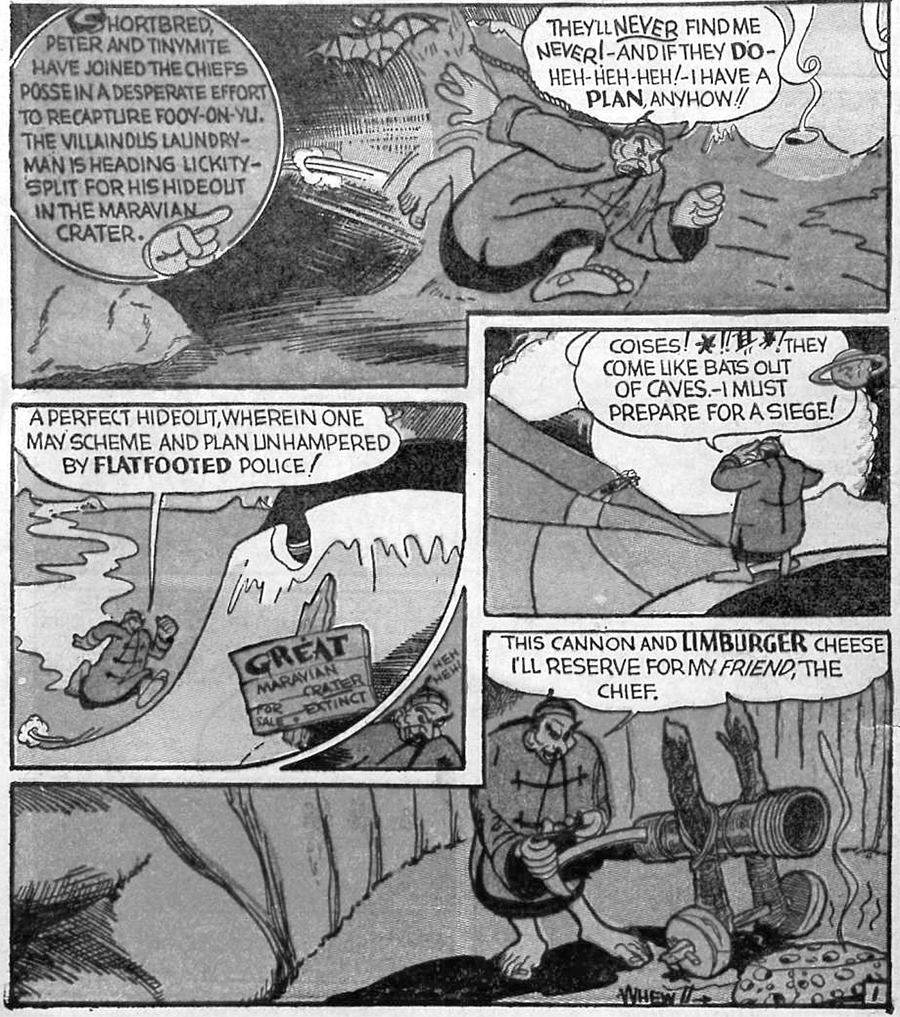

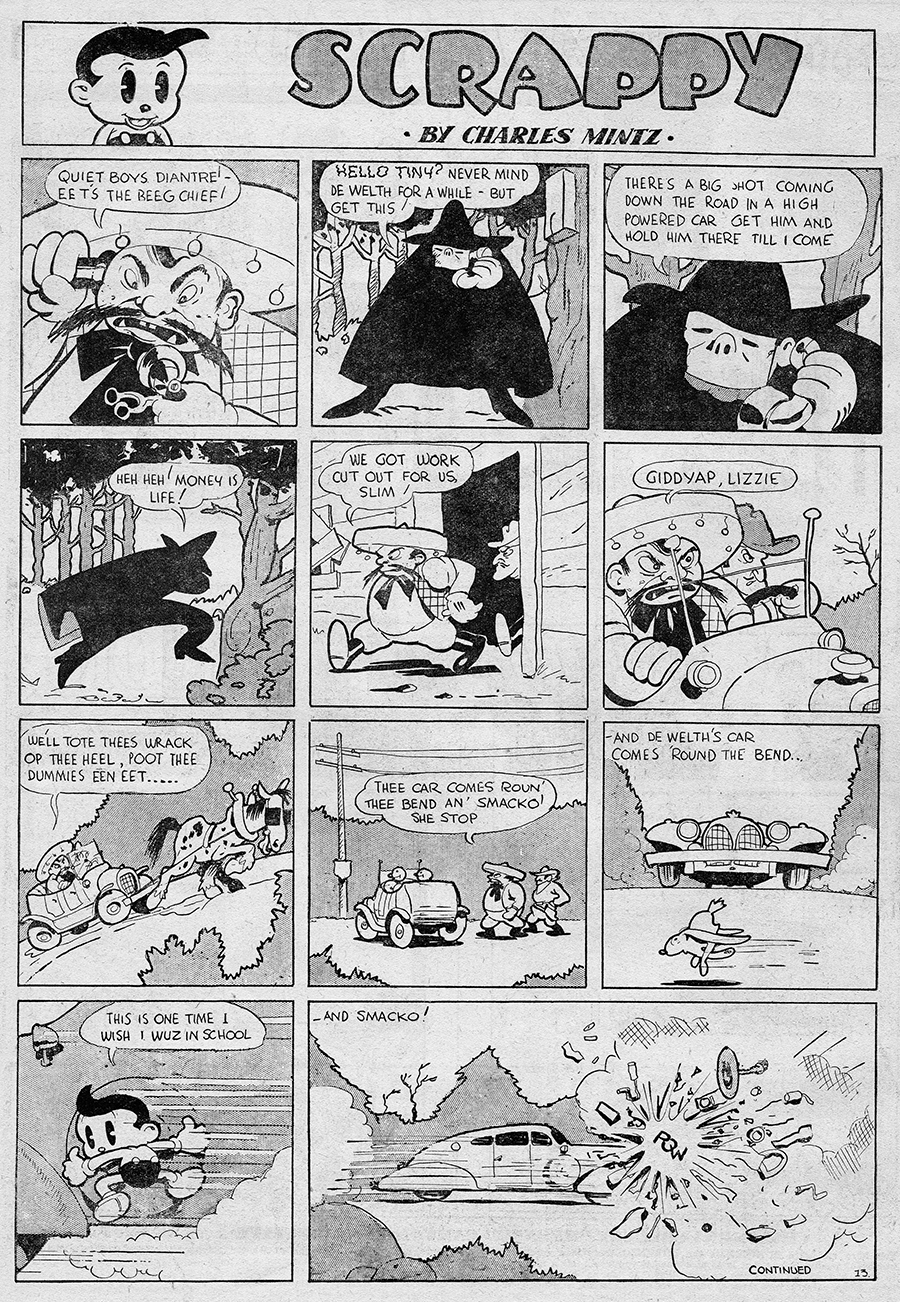

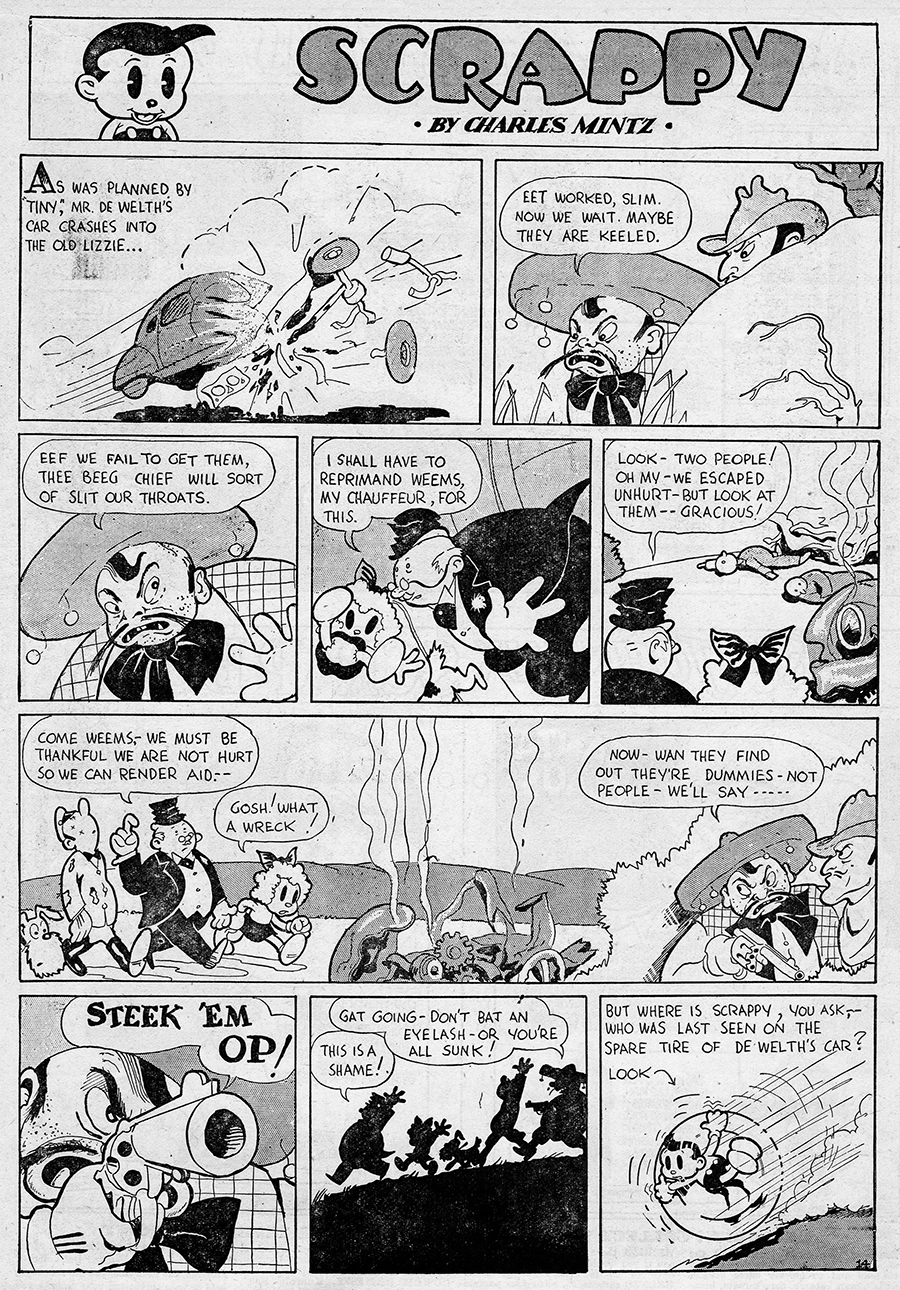

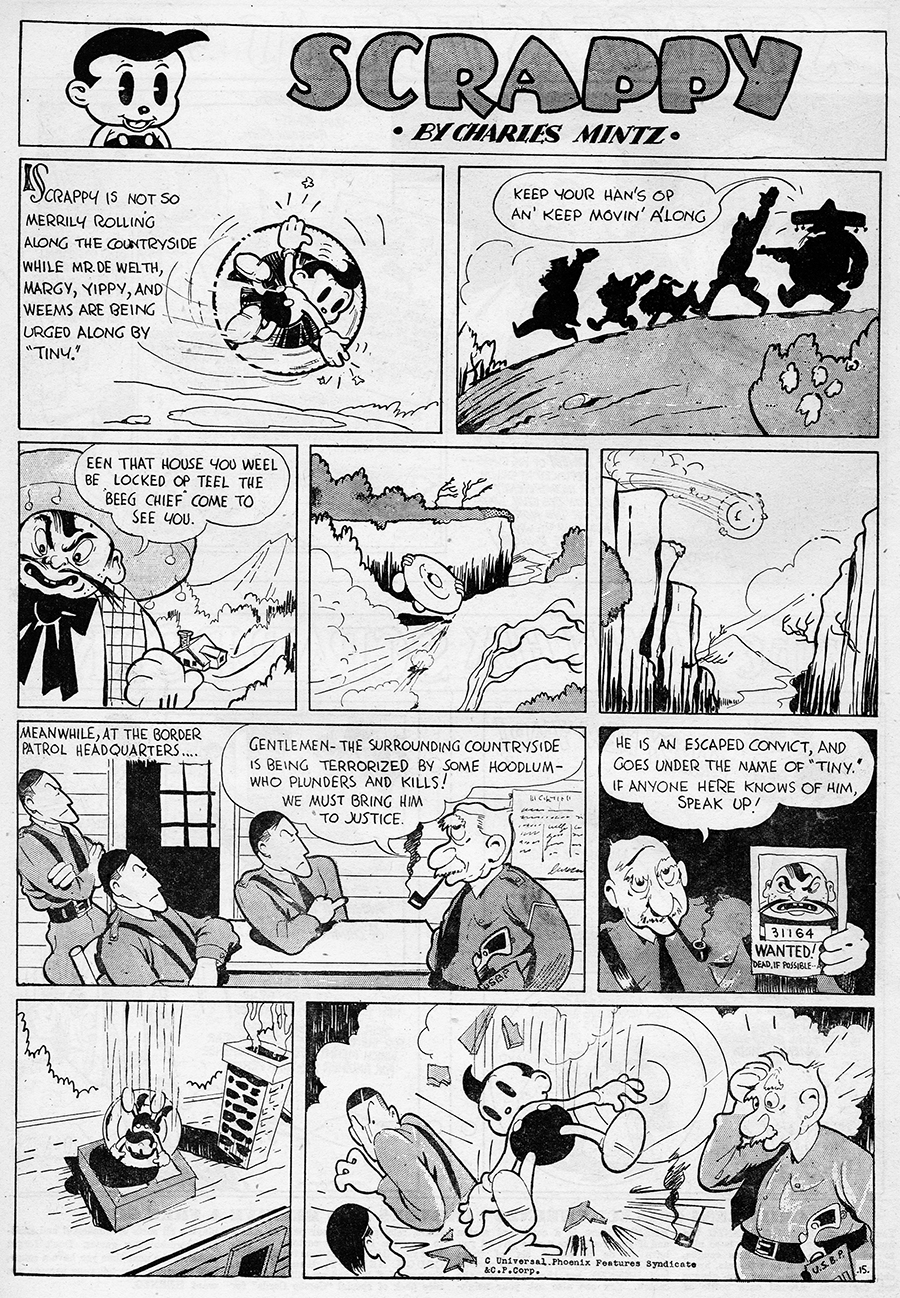

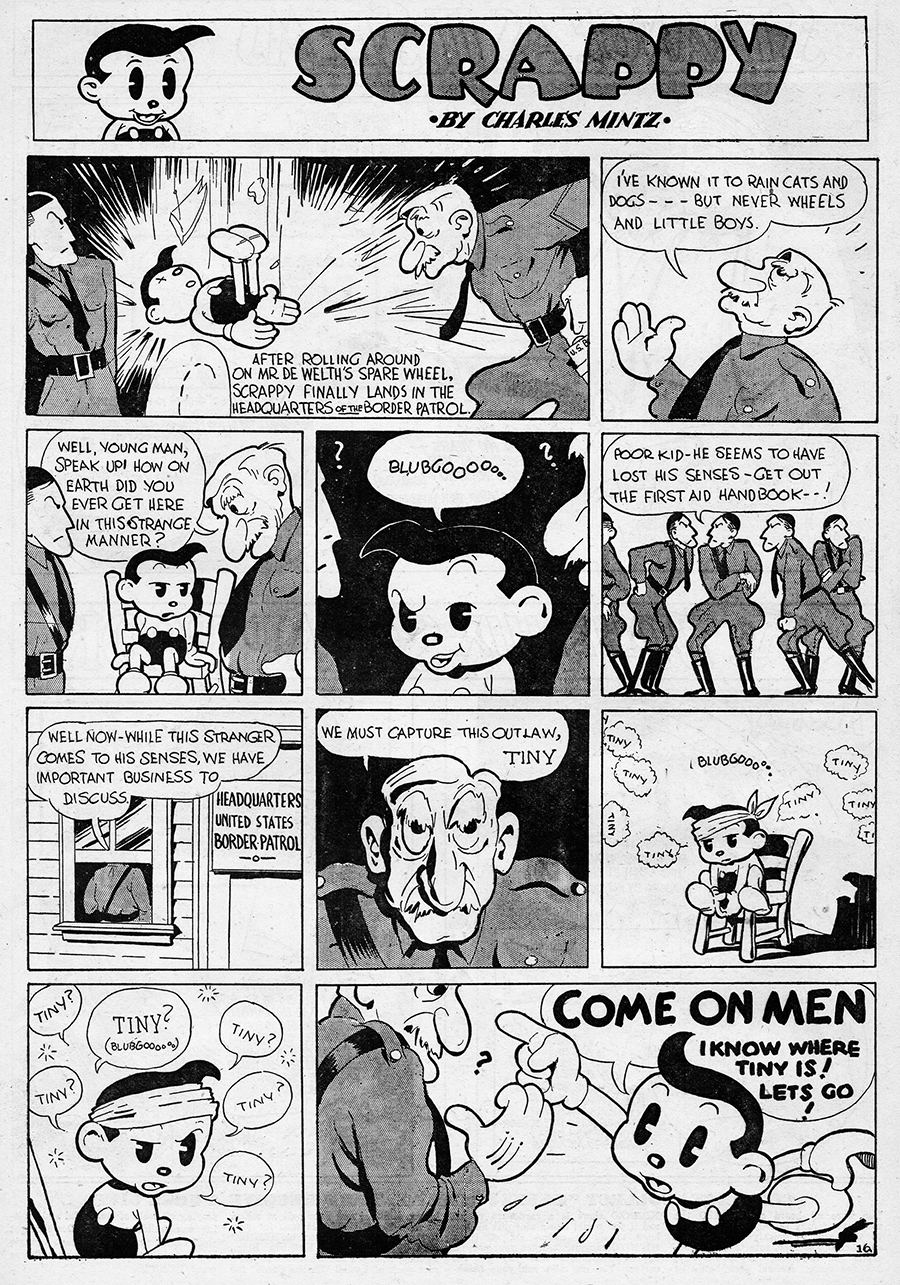

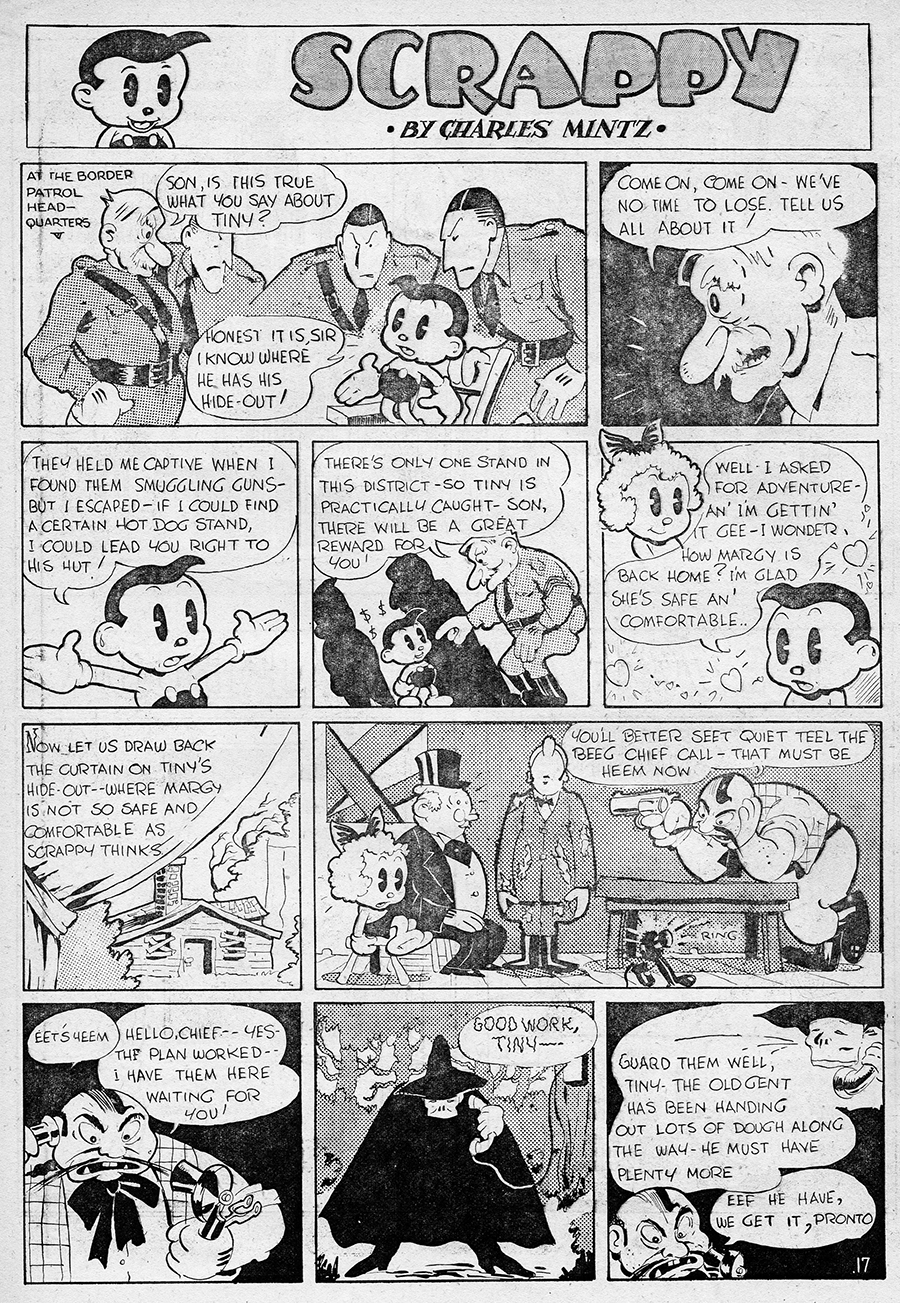

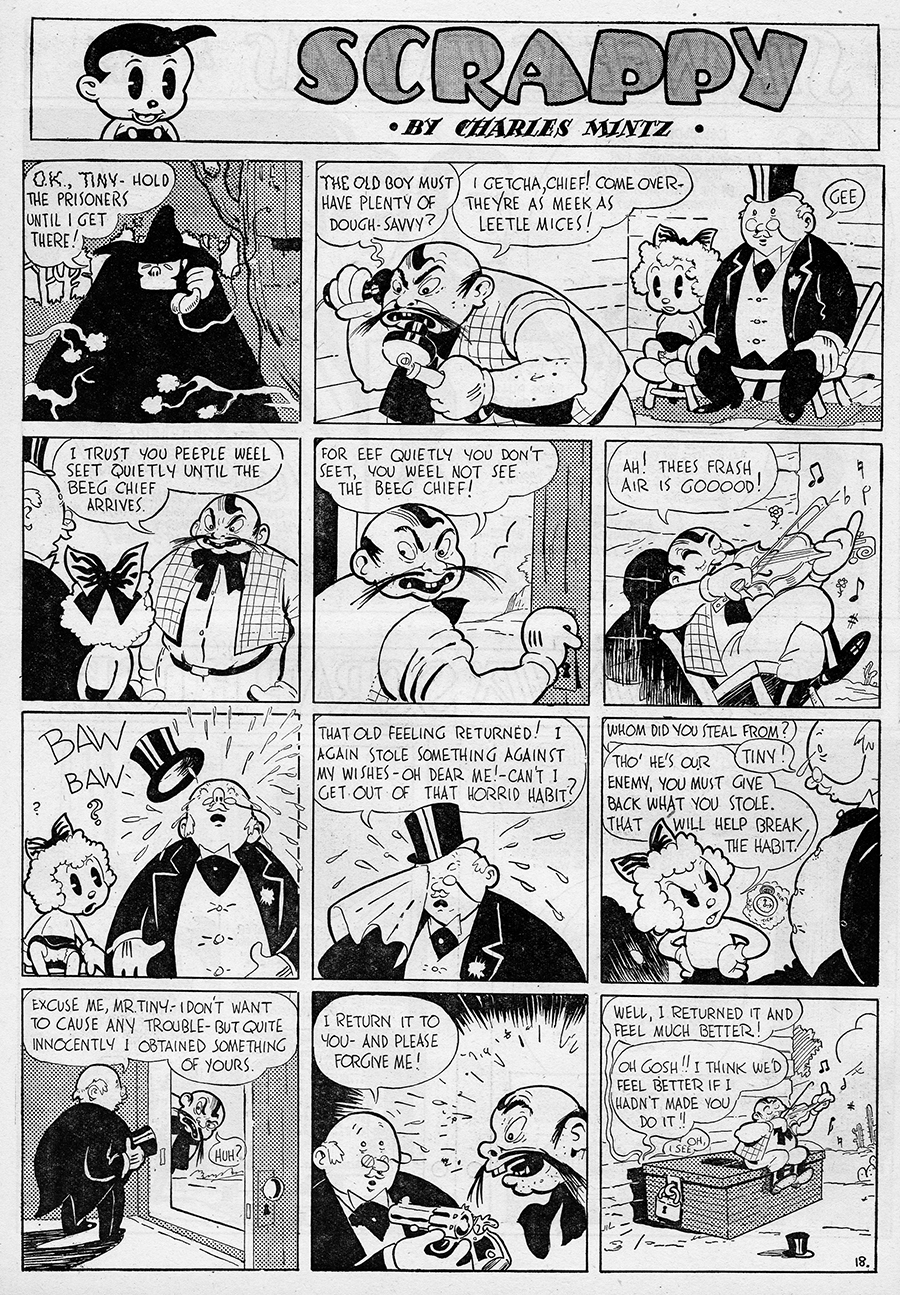

You look like you’d enjoy a good Scrappy story. Here’s one from 1932—the start of one, at least.

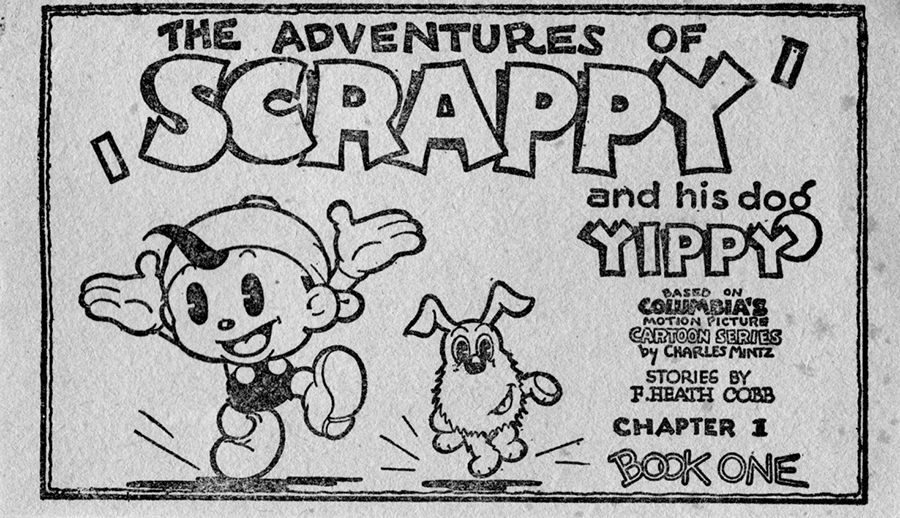

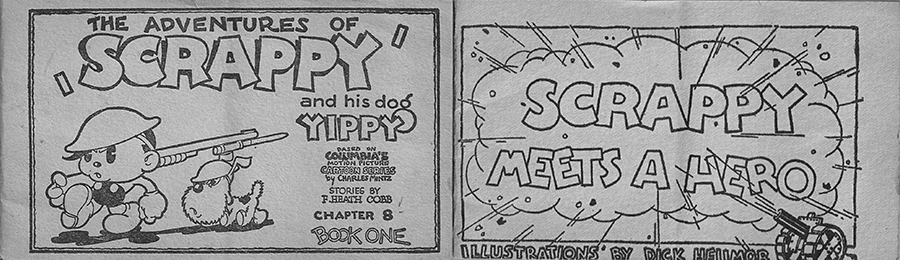

More specifically, it’s Chapter 1 of Book One of The Adventures of ‘Scrappy’ and His Dog Yippy—written by F. Heath Cobb and illustrated by our friend Dick Huemer (working under his occasional pen name of Dick Heumor, which he adopted because it hoped it would help people figure out how to pronounce his name—which it didn’t).

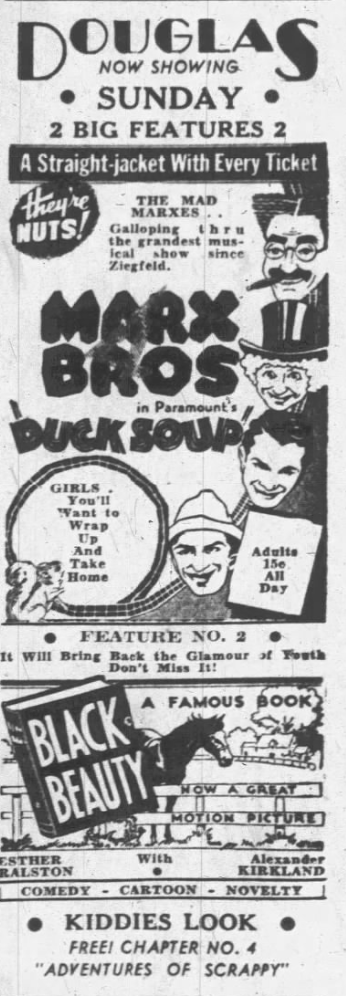

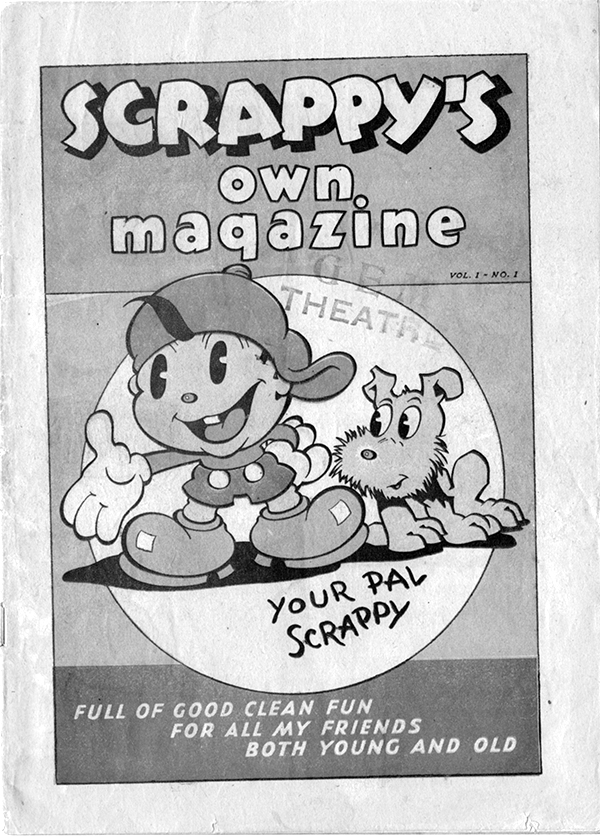

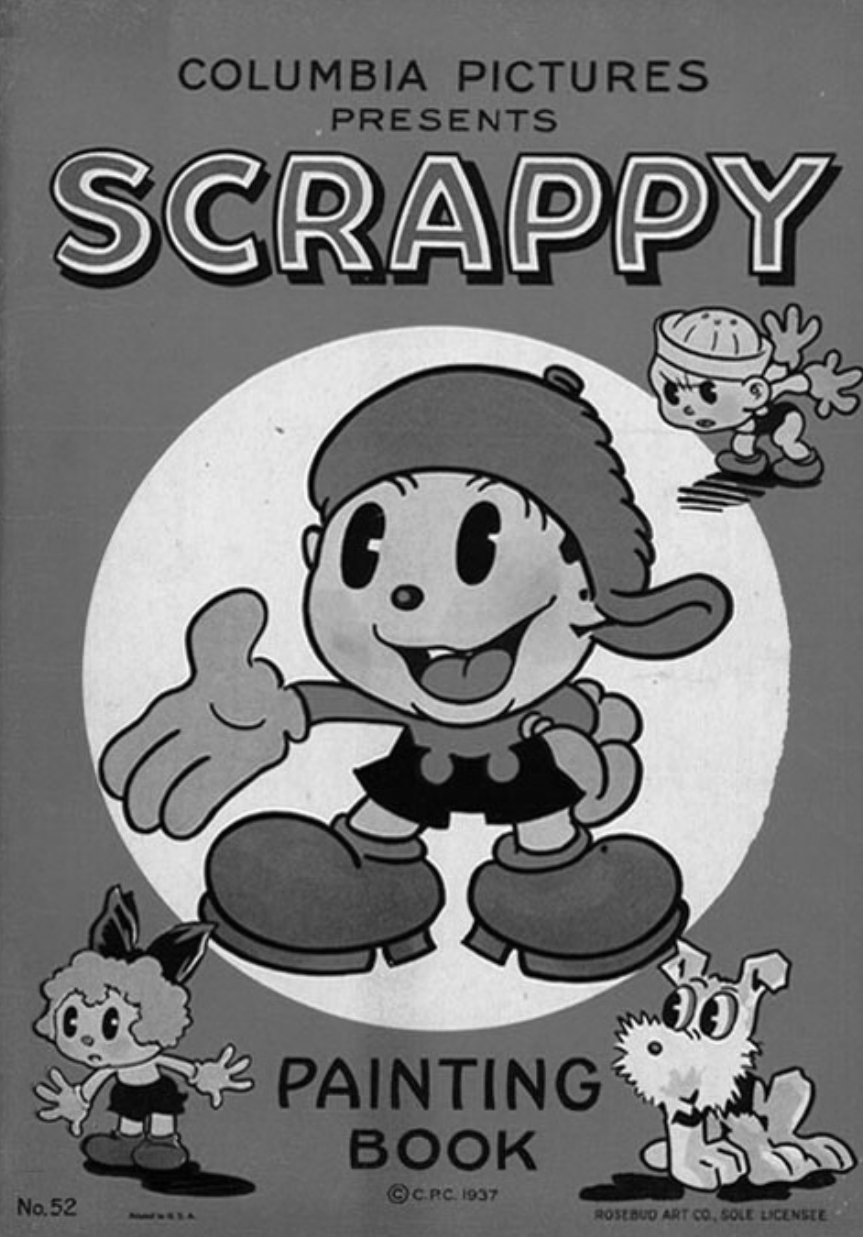

While this would seem to be the first Adventures of ‘Scrappy’ booklet, it’s the second I’ve shared (here’s the earlier one). I don’t know much about them other than that they were given away at theaters. How many booklets there were, I can’t say. But in all my years of Scrappy collecting, I haven’t seen that many for sale. Unless I find a copy of Book One, Chapter 2, someday, we may never learn what happened to Scrappy and Yippy at their fishing party, and for that, I apologize in advance.

Oh, and as I wrote back in the early days of Scrappyland—and forgot until I looked it up just now–these booklets were also included in Scrappy paint sets.

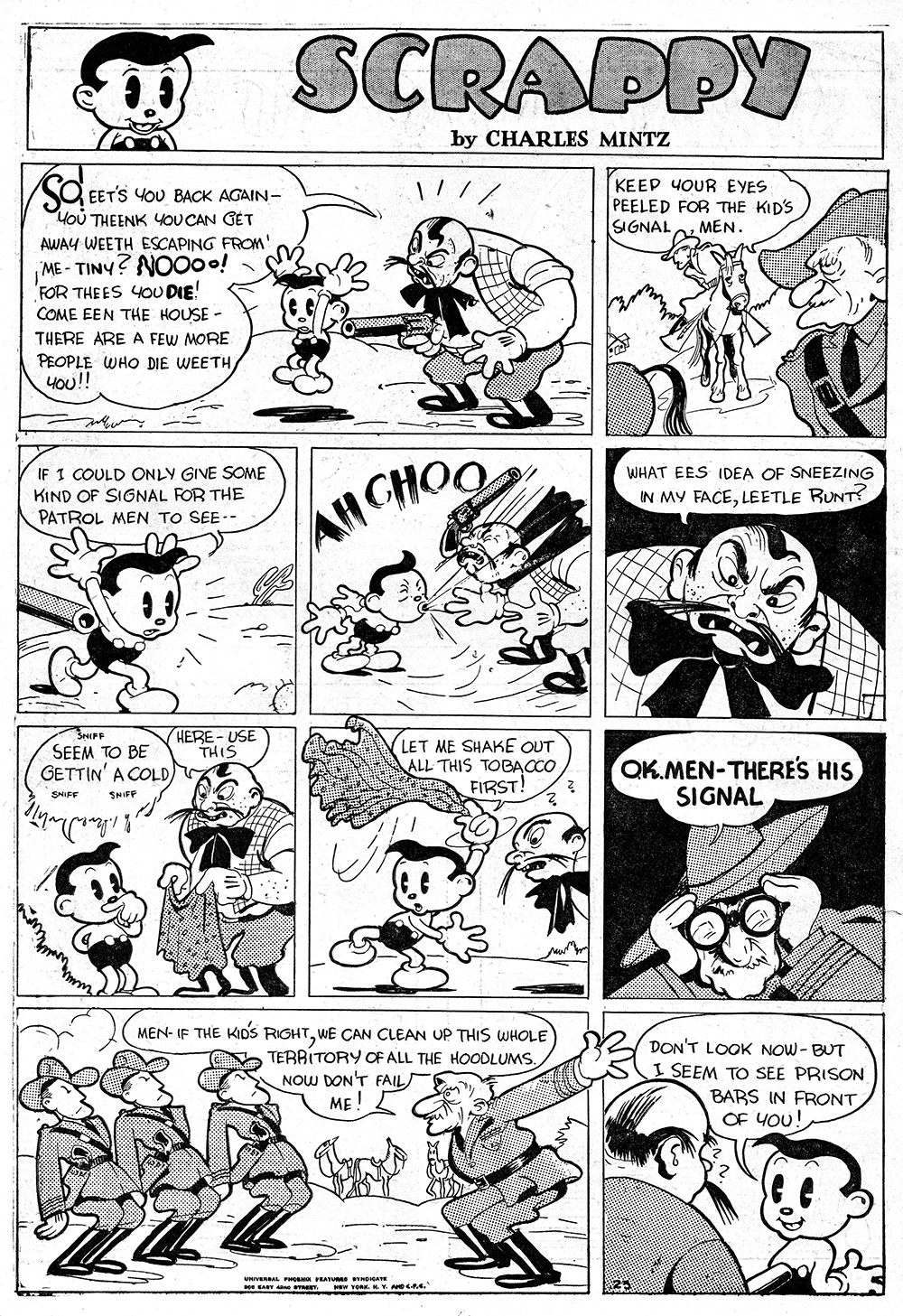

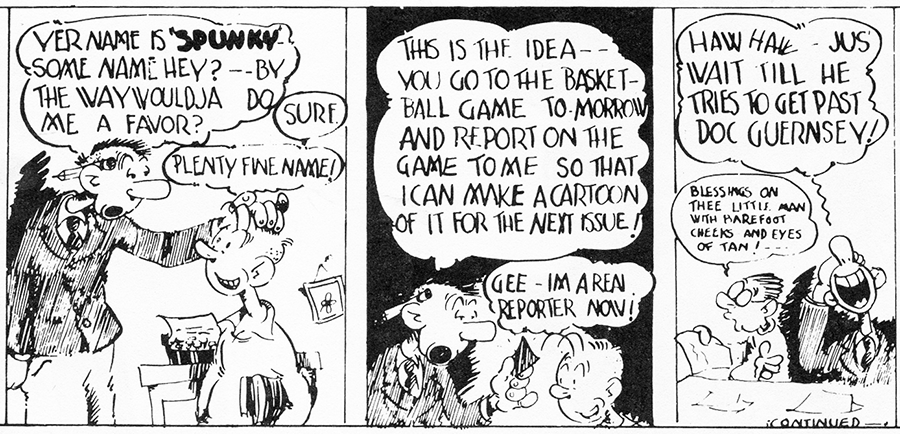

But really, the main reason I’m writing this is not to talk about The Adventures of ‘Scrappy.’ My topic today is F. Heath Cobb. Along with writing these Scrappy booklets, he was the author of How to Draw a Cartoon, an instructional pamphlet—credited to Scrappy himself—distributed through schools. (It’s less interesting than it sounds, which is why I haven’t gotten around to writing about it here yet—I will someday, I promise.)

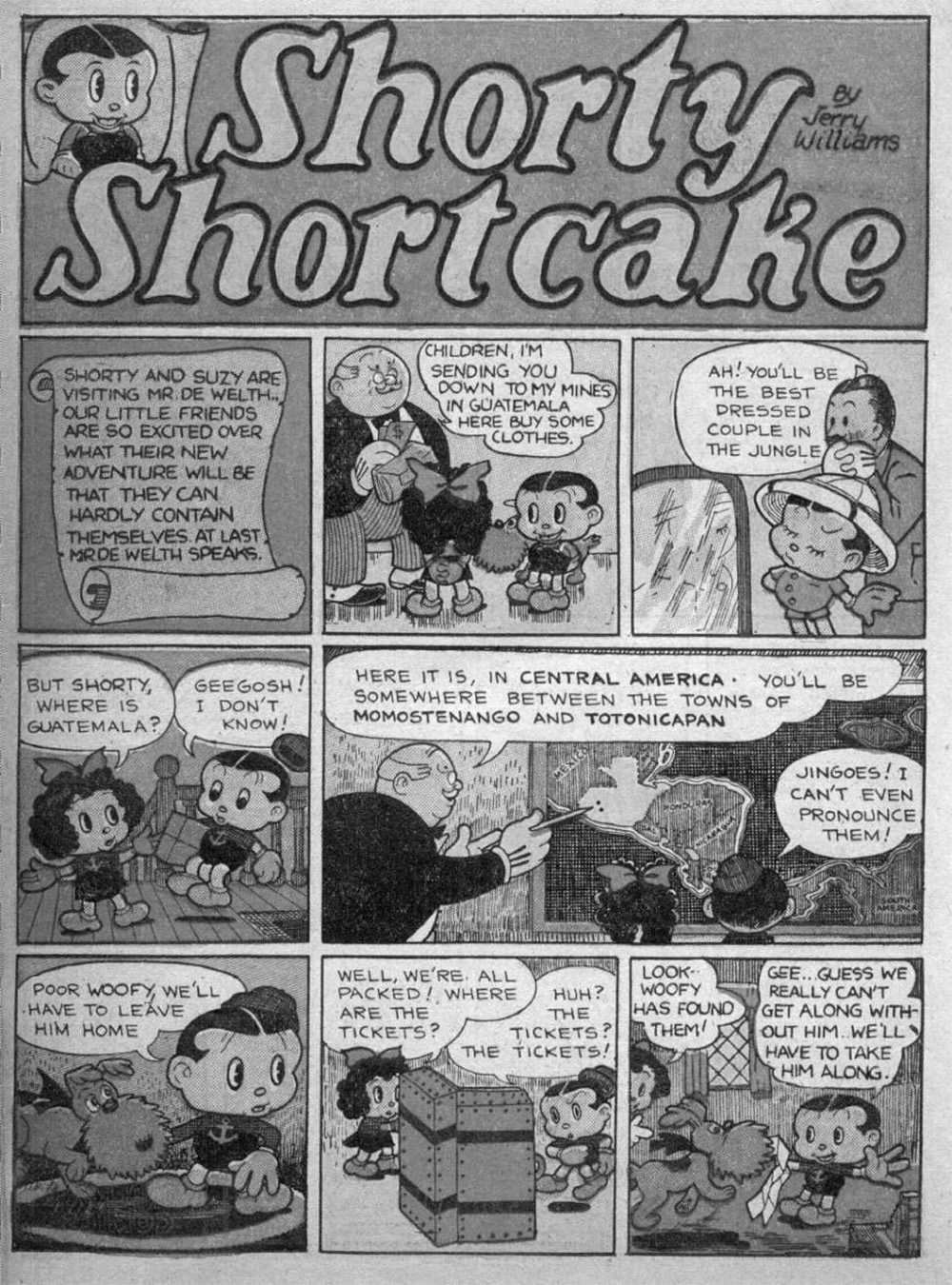

Cobb wasn’t the only author credited with writing a Scrappy book. Pat Patterson wrote the Scrappy Big Little Book, and Hal Hode was responsible for a BLB-esque book from another publisher. But as the author of several adventures of Scrappy serialized through multiple booklets, Cobb must have been bylined on more Scrappy publications than any other scribe. He also had a wonderfully evocative name. It brings to mind a man of accomplishment—the author of works other than Scrappy booklets, surely. Maybe a bit of a toff.

Still, I couldn’t be positive that “F. Heath Cobb” wasn’t some sort of house pseudonym along the lines of Burt L. Standish, the author of the Frank Merriwell books. So I set out to learn if he was a real person—and if so, what he did with himself other than write Scrappy books.

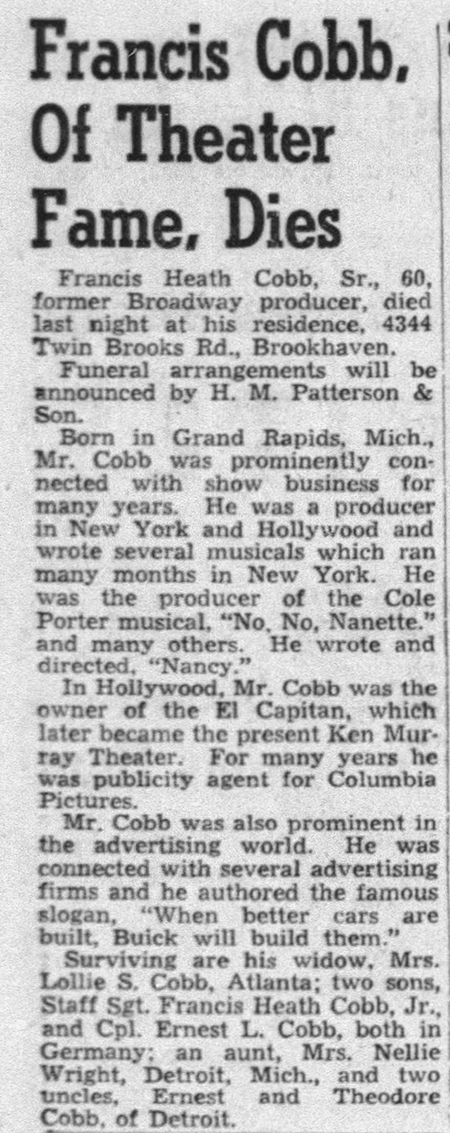

It turns out that there have been more F. Heath Cobbs than you might expect. Take, for instance, the one who taught at a community college in Tacoma in the 1970s. He seemed like an unlikely candidate to be chronicling Scrappy’s adventures forty years earlier. But with a bit of rummaging on Newspapers.com, I found this January 9, 1949 Atlanta Constitution obituary:

A long-time publicity agent for Columbia? This is our Cobb. Scrappy’s Cobb.

Though the obit didn’t mention Cobb writing Scrappy books, it did cover a lot of other ground. Producer of the Cole Porter musical No, No, Nanette. Writer and director of other musicals. Owner of Hollywood’s famous El Capitan Theater. Prominent ad man. Father of two—here he is, on the right, with F. Heath Cobb Jr. (who, it turns out, was the aforementioned Tacoma professor).

When I tried to dig into all this, I usually didn’t get very far. For instance, I couldn’t find any evidence that Cobb owned the El Capitan (which does have a roundabout association with Charles Mintz: It’s now a Disney property). Maybe he came up with Buick’s long-running tagline, but I saw mention of that achievement only in his death notices. I am also suspicious about the claim that he produced anything for Broadway, including No, No, Nanette (which wasn’t actually by Cole Porter).

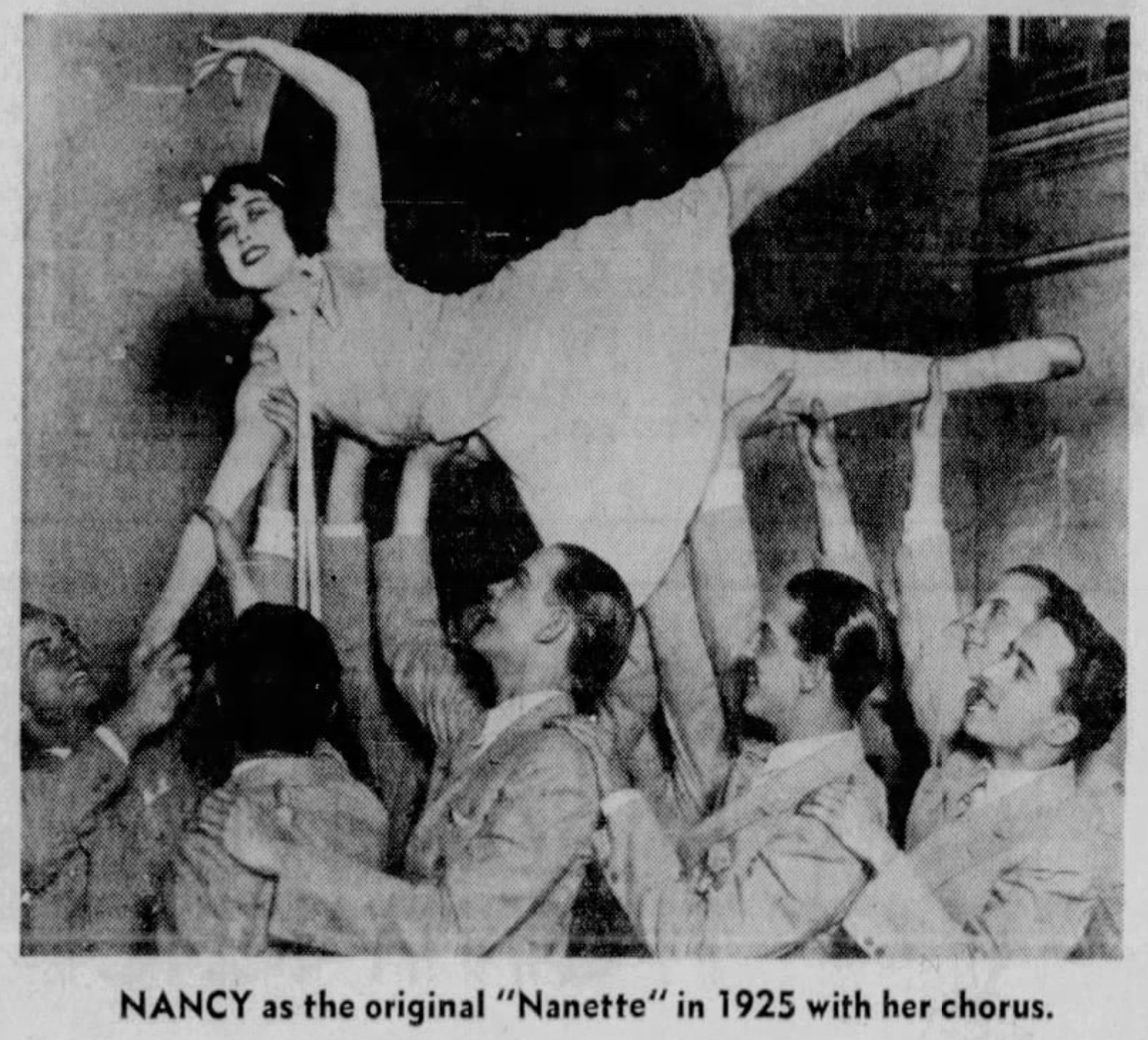

Still, Cobb did have a Nanette connection: He was married to Nancy Welford, a former Zigfield Girl who’d starred in one of several productions of the wildly popular musical that played simultaneously in 1925. Hers got to San Francisco and Los Angeles, at least. Decades later, stories about her identified her as the original Nanette (no) and said she’d played the role on Broadway (not that I’ve been able to verify).

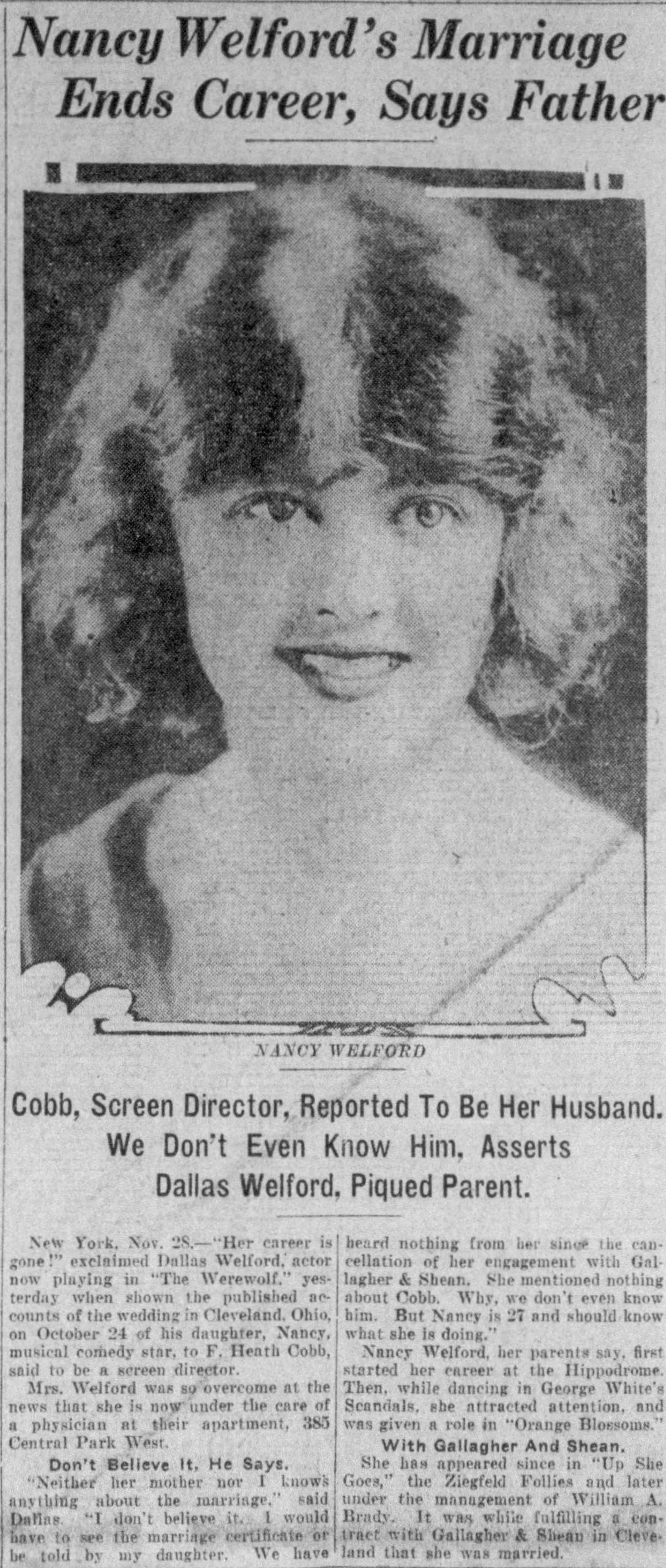

When Cobb and Welford married in October 1924, it had made headlines—in part because she was already a celebrity but also because her parents claimed to be in disbelief. It was Welford’s first marriage but—according to one Ancestry.com family tree—Cobb’s fifth. A 1922 article, which cited his “smart clothes and irresistible manner,” said he’d gotten in trouble for marrying one of his wives before divorcing the prior one. He also narrowly avoided being prosecuted for impersonating an Army Captain; charges weren’t pressed because he’d sold $250,000 of Liberty Bonds.

Do you begin to understand why Mr. and Mrs. Welford weren’t thrilled with the idea of their daughter marrying this guy?

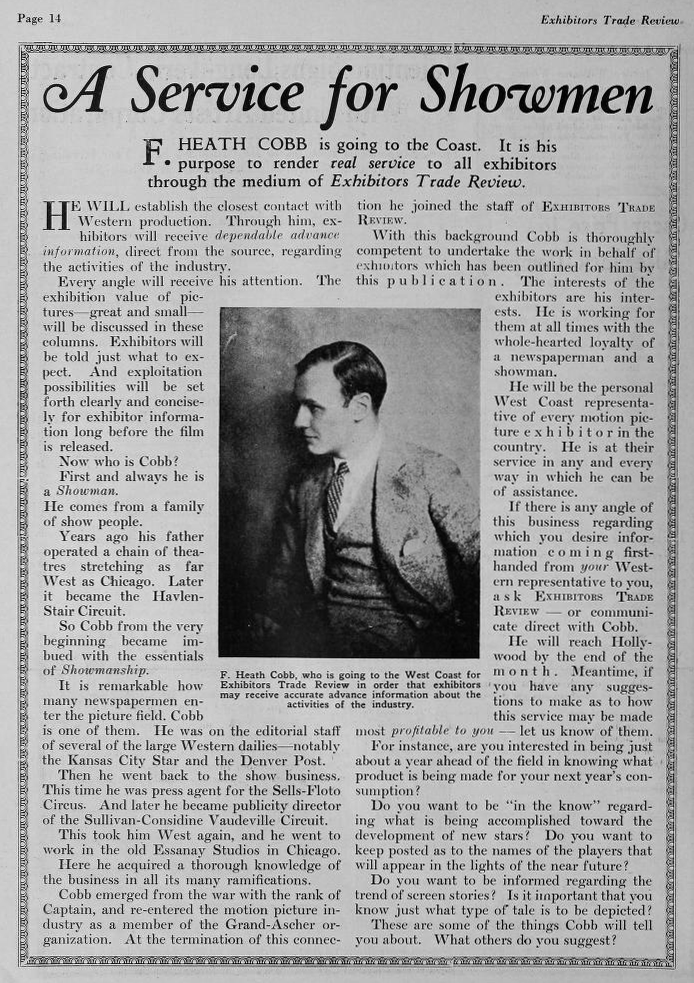

Note that the above story identified Cobb as someone “said to be a screen director,” adding to the general mystery about the man’s actual profession. A 1925 article about him, published in a trade publication he’d joined, provided more details about his background—child of show people, newspaperman, circus, vaudeville publicist, employee of Essanay Studios. But given that it repeats his apparently spurious claim of having been an Army Captain during the Great War, I’m not sure what to believe.

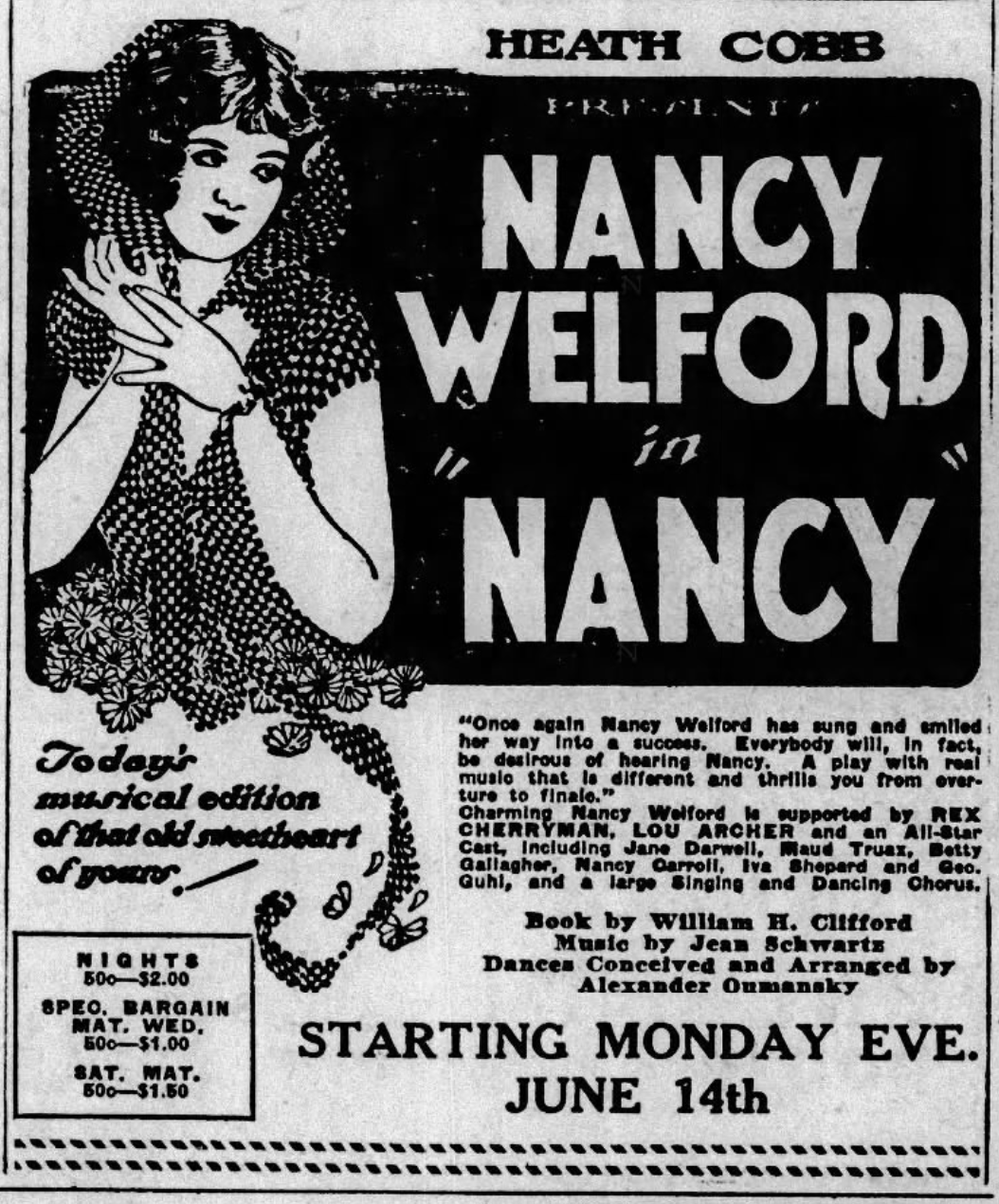

Getting back to the Cobb obit: Its mention of his involvement with a musical called Nancy is one of its few alleged factoids that definitely is accurate, more or less. By now, you’ve guessed that the show starred Nancy Welford, who supposedly inspired it. According to The Los Angeles Times, she played “a little country girl bent upon spreading happiness.” Other articles on the production compared it to Pollyanna and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm.

Unfortunately for Cobb and Welford, Nancy was “not a pronounced success in any of the cities where it was shown,” reported a Seattle Star story. After tryouts in Long Beach, the show premiered at Los Angeles’s Playhouse Theater on May 24, 1926. On June 14, it opened in San Francisco. A little over two weeks later, newspaper accounts said it was about to begin its final week. Even that was apparently cut short when the chorus walked out in a salary dispute.

As far as I know, Cobb’s career as a theatrical producer did not survive Nancy‘s disappointing reception. But as the 1920s wound down, Welford continued to perform in stage musicals, including Twinkle Twinkle (with Joe E. Brown) and a light opera called Bambina. In 1929, she made her movie debut in Gold Diggers of Broadway—the second all-talking, all-Technicolor picture. (Sadly, only two reels survive.) I’m guessing this publicity shot, depicting her literally digging gold, relates to the film.

Gold Diggers of Broadway was a big hit, but Welford only made four more movies. By 1933, her Hollywood career was over.

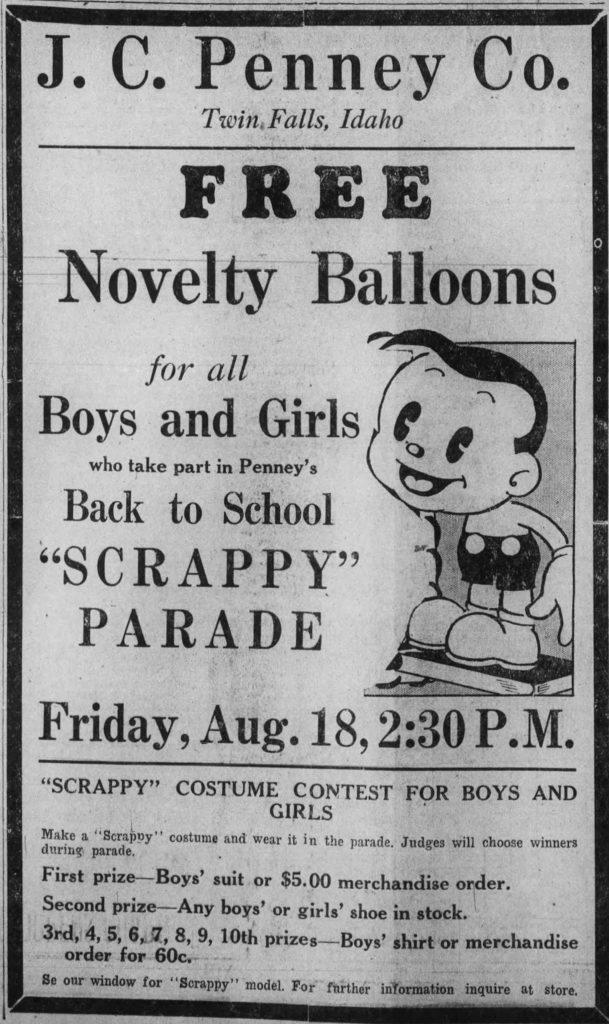

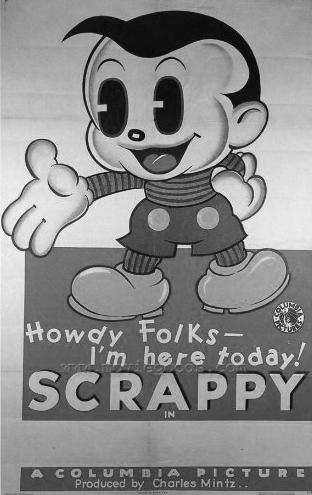

Meanwhile, Cobb had already returned to the PR work he’d pursued before marrying her. A 1930 Exhibitors Herald World story noted he was involved with the promotion for a revival of (ugh) D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. In 1931, the Motion Picture Daily reported that he had joined Columbia’s advertising department. And in 1932 and 1933, newspaper articles—ones possibly planted by him—said he was the First Assistant National Chief Ranger of the Buck Jones Rangers Club, a fan group for the studio’s cowboy star.

This was also the same timeframe when Cobb wrote Scrappy books. We can assume he got the gig as part of his Columbia publicity duties. But I’d love to know: Was he just being dutiful? Or did he eagerly seize the opportunity to tell Scrappy stories? Maybe he had some measure of interaction with Mintz studio personnel—Dick Huemer, at least, since he illustrated the booklets. We’ll probably never know. But I prefer to believe he enjoyed the project. After all, he did choose to take credit for it.

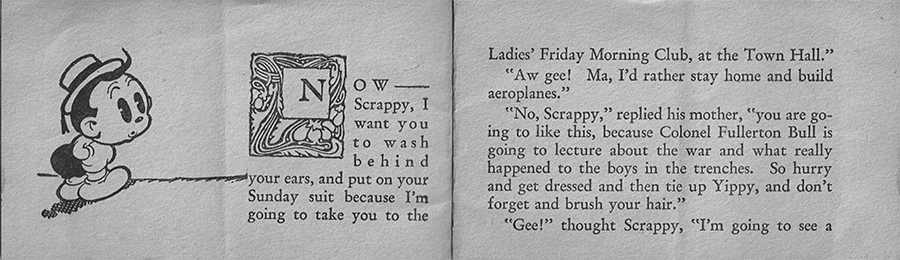

And hey, in Chapter 8 of “The Adventures of ‘Scrappy,'” Cobb may have told a story with an oddly autobiographical angle. Book One, “Scrappy Meets a Hero,” involved him getting the chance to hear a WWI vet explain “what really happened to the boys in the trenches.” I don’t have this booklet—just some sample pages from an old auction listing. But the vet’s name–”Colonel Fullerton Bull”—hints at the tantalizing possibility that he, like Cobb, wasn’t a war hero after all.

Increasingly, Cobb made the news for reasons no PR man would seek out. In January 1928, The Los Angeles Times said that he and Welford had lost a suit brought by Fred Hartsook, a well-known Hollywood photographer, over a $910 bill they hadn’t paid. In 1934, Variety reported on a scandal Cobb was involved in that does sound pretty scandalous: He admitted to having forged the signatures of Claudette Colbert, Carole Lombard, Myrna Loy, Sylvia Sydney, Mae West, and other stars on contracts to endorse a hosiery firm he represented. (He claimed he did it “to save time,” confident that he could gain their consent later.) Later in the month, Variety noted that Cobb and Welford had been sued again, this time over an unpaid $150 clothing bill at a New York store.

That last item is the final one I’ve found indicating that Cobb and Welford were still married. At some point, possibly around then, they split up. Cobb went on to wed wife #6. He mostly disappeared from newspapers by the mid-1930s, but in 1946, at least a couple of newspapers published an anti-union letter from an F. Heath Cobb of North Augusta, S.C. I think he may be our man, engaging in what we’d now call astroturfing. In any event, I’m curious what brought him to Atlanta, where he died three years later.

As for Welford, she too remarried. She also worked as a sales clerk in San Francisco, did local theater in the Bay Area (including some Gilbert and Sullivan), and enjoyed being remembered for No, No, Nanette, especially after its 1971 Broadway revival. You’ve already seen that she wasn’t mentioned in Cobb’s obituary. And when she died in 1991—more than 40 years after her ex-spouse—he was absent from hers.

I seem to have fallen down a rabbit hole here, as we so often do on Scrappyland. As usual, it’s been a rewarding experience. If there are Scrappy books written by someone named F. Heath Cobb, you know there’s going to be a story behind the intriguing name. And it will probably be even weirder than whatever pops into your head. Or did you naturally assume he was an oft-married fabulist and failed impresario?